The era of fingerprint scanners for employee attendance in Spain is over. Following the AEPD's November 2023 guidelines and a series of devastating enforcement actions, biometric timekeeping systems now face a de facto prohibition for most Spanish businesses. Here's what you need to know:

Bottom line: If you're running a gym, language academy, construction site, or any SME using fingerprint scanners for attendance—you're sitting on a compliance time bomb. This article explains why the regulatory ground has shifted beneath your feet and what you must do now.

For years, Spanish business owners believed they'd found the perfect solution to attendance fraud: the fingerprint scanner. Quick, cheap, impossible to forget at home, and seemingly more secure than cards or PINs. Thousands of gyms, language schools, factories, and offices deployed these systems with confidence.

That confidence was misplaced.

In November 2023, Spain's data protection authority (Agencia Española de Protección de Datos, or AEPD) published guidelines that fundamentally redefined the legal landscape for biometric attendance systems. What followed was a enforcement campaign that turned fingerprint scanners from standard business tools into regulatory liabilities carrying six-figure fines.

The AEPD's message is unequivocal: biometric attendance systems cannot meet the legal requirements for processing special category data in almost any business context. This isn't a minor compliance tweak, it's a complete prohibition for the vast majority of Spanish companies.

Before November 2023, many businesses operated under a crucial misunderstanding. They believed that biometric authentication (one-to-one matching, where your fingerprint unlocks "your" record) was different from biometric identification (one-to-many matching, where the system searches a database to identify you). The conventional wisdom held that authentication didn't involve processing "special category" personal data under Article 9(1) GDPR.

The AEPD's guidelines shattered this distinction.

Following the European Data Protection Supervisor's Guidelines 05/2022 on facial recognition in law enforcement, the AEPD adopted a radical new position: both biometric identification and biometric authentication constitute processing of special category data. Whether your system matches one fingerprint to one employee record, or searches through a database of thousands, makes no difference. Both fall under the blanket prohibition in Article 9(1) GDPR.

This matters because Article 9(1) GDPR establishes a general prohibition on processing biometric data. You can only process such data if you meet one of the narrow exceptions in Article 9(2), and as we'll see, those exceptions are nearly impossible to satisfy for attendance tracking.

In what became the defining case, SIDECU S.A.—operator of the Supera sports centre chain—replaced its card-and-fingerprint access system with mandatory facial recognition. Members weren't informed, weren't consulted, and weren't given alternatives.

When complaints flooded in, SIDECU doubled down. They argued that neither fingerprints nor facial recognition images were "stored," therefore no personal data was being processed. The AEPD demolished this argument, explaining that biometric templates—the mathematical patterns derived from biometric data—are themselves special category personal data.

The AEPD imposed a fine of €96,000 and ordered immediate suspension of biometric processing. But the real precedent was established: the convenience of biometric systems doesn't justify their use when alternatives exist.

This gym required members to use fingerprints for facility access. The case established three critical violations:

Most damningly, the AEPD found that the gym couldn't justify why fingerprints were necessary when card-based access would achieve the same security objective. The investigation revealed the gym also failed to delete a complainant's biometric data after membership cancellation—compounding the breach.

The lesson: "It's more convenient" and "members signed a contract" are not legal bases for processing biometric data.

This outsourcing company implemented fingerprint scanning for employee time registration. They confidently told the AEPD that they used an "authentication system, not identification," and that fingerprints weren't stored—only encrypted numeric identifiers were retained.

The AEPD wasn't impressed. The authority found violations of:

The €360,000 fine sent shockwaves through Spanish businesses. The AEPD explicitly noted the "high sensitivity of biometric data" and the prolonged duration of the violation (over two years).

The lesson: Technical arguments about "templates versus fingerprints" won't save you. If biometric data was ever involved in creating those templates, you're processing special category data.

In the most spectacular case, LaLiga (Spain's professional football league) issued regulations requiring clubs to implement biometric access for "animation stands"—the sections reserved for the most passionate fans. Patrons had to submit to fingerprinting or facial recognition and provide consent at the point of entry, or be denied access.

LaLiga argued it was merely providing clubs with an optional system. The AEPD disagreed, determining that LaLiga was the data controller and imposing a €1,000,000 fine for failing to conduct a proper DPIA that would assess the necessity and proportionality of the processing.

The authority also ordered immediate suspension of biometric processing until an appropriate DPIA could demonstrate that less intrusive alternatives were genuinely impossible.

The lesson: Even when processing appears to be for legitimate security purposes (preventing stadium violence), if alternatives exist, biometrics fail the proportionality test.

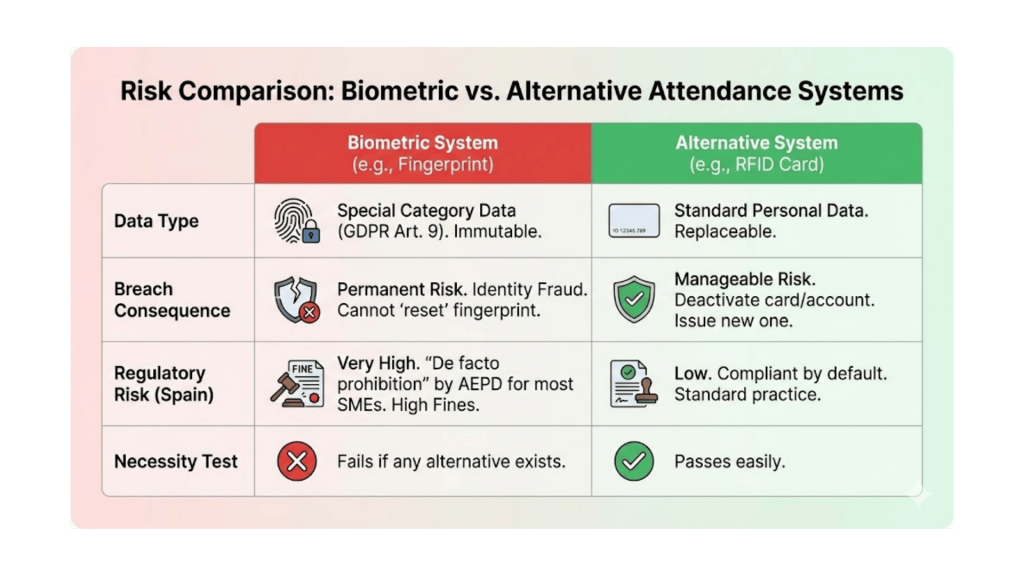

At the heart of the AEPD's hardline stance is a fundamental characteristic of biometric data: you can't change your fingerprints.

When your password is compromised, you change it. When your credit card is stolen, you cancel it and get a new one. When your RFID badge is lost, you deactivate it and issue a replacement. These are all reversible, controllable, replaceable identifiers.

But your fingerprints? You're born with them and you'll die with them. If your biometric data is breached—through a database hack, insider threat, or system vulnerability—you cannot "reset" your fingerprints. The compromise is permanent and opens you to identity fraud for life.

This immutability creates what data protection law calls "high risk" to the rights and freedoms of individuals. The GDPR specifically requires enhanced protections for such high-risk processing, including mandatory DPIAs and heightened security measures.

The AEPD has made clear: this inherent risk cannot be justified by the marginal convenience gain of not having to carry a card or remember a PIN.

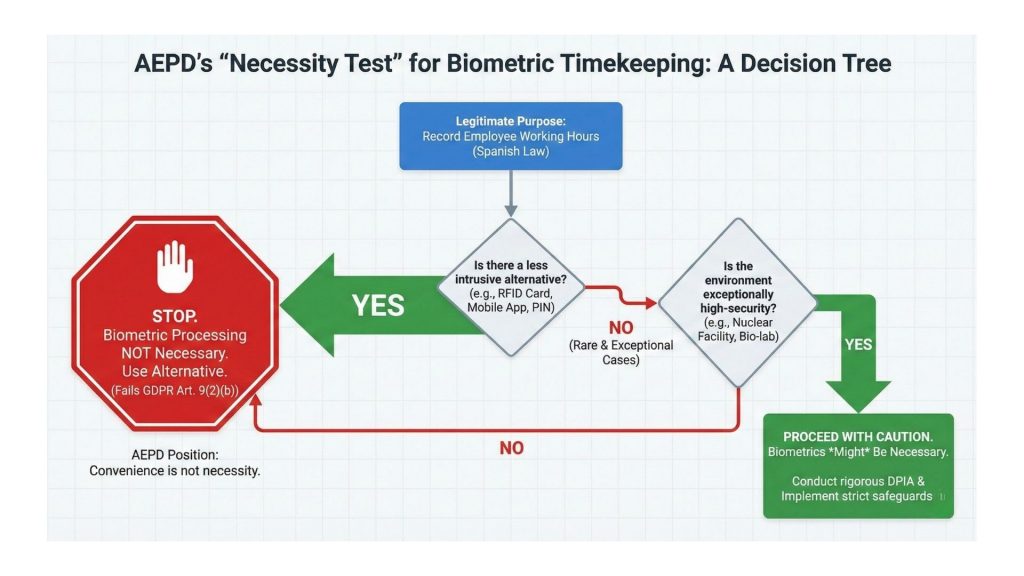

Article 9(2)(b) GDPR provides an exception to the biometric data prohibition: processing is allowed when it's "necessary for the purposes of carrying out the obligations and exercising specific rights of the controller or of the data subject in the field of employment."

Notice that word: necessary.

Spanish law (Real Decreto-Ley 8/2019) does indeed require employers to monitor and record employee working hours. This obligation was introduced to combat unpaid overtime and ensure labour protections. So at first glance, biometric timekeeping seems to satisfy the necessity test.

But here's the critical distinction the AEPD makes: the law requires monitoring working hours, not monitoring fingerprints.

The necessity test asks: "Is there any other way to achieve this legitimate purpose that doesn't involve processing special category data?" If the answer is yes—and it almost always is—then biometric processing is not necessary.

The AEPD guidelines explicitly identify less intrusive alternatives:

Each of these alternatives achieves the same purpose—recording when employees start and end work—without processing biometric data. And that's the problem for businesses defending fingerprint systems: the AEPD has concluded that if any viable alternative exists, biometric processing cannot be deemed "necessary."

The AEPD acknowledges there may be rare scenarios where biometrics genuinely are necessary—but they set an extraordinarily high bar.

The guidelines suggest biometric processing might be justified in contexts like:

Notice what's missing from this list: gyms, academies, construction sites, warehouses, offices, retail shops, and essentially every normal business environment.

Unless you're operating a nuclear reactor or guarding state secrets, you cannot justify biometric timekeeping.

Some businesses have tried to argue: "Our employees consented to fingerprint scanning when they signed their contracts. Article 9(2)(a) allows processing with explicit consent."

The AEPD has comprehensively rejected this argument.

GDPR requires consent to be "freely given"—but in employment relationships, there's an inherent power imbalance. An employee who needs their job cannot freely consent to processing their employer demands. The fear of consequences (being seen as difficult, missing promotions, or facing dismissal) means consent given in an employment context is inherently coerced.

The European Data Protection Board made this explicit in Guidelines 05/2020: "in general, there is an imbalance of power between employee and employer that means this consent is not freely provided and should therefore not be the legal basis."

But the AEPD goes further. Even if you could somehow demonstrate that consent was truly free (perhaps by showing that rejecting biometrics had no consequences), you'd still fail the necessity test.

The logic is circular but inescapable: If you offer employees an alternative method (cards, PINs, etc.) to prove consent is freely given, then you've just demonstrated that biometrics aren't necessary—because the alternative method works.

And if an alternative method works, then processing biometric data fails the data minimisation principle in Article 5(1)(c) GDPR. You must always use the least intrusive means to achieve your purpose.

Some businesses have tried a hybrid approach: "Employees can choose fingerprint scanning OR card access—their choice!"

The AEPD has been skeptical of this too. The guidelines ask: if the card system works adequately for employees who decline biometrics, why not use the card system for everyone? What purpose does the biometric option serve that justifies the additional risk?

The answer is usually "convenience", and as we've seen repeatedly, convenience alone doesn't satisfy the necessity and proportionality tests for processing special category data.

Article 35 GDPR requires a DPIA whenever processing is likely to result in high risk to individuals' rights and freedoms. Processing biometric data—especially of employees, who are considered a vulnerable group—is automatically high risk.

A compliant DPIA must demonstrate that your biometric system passes the triple test:

Does the biometric system actually achieve your stated purpose? In most cases, yes—fingerprint scanners do record attendance and prevent buddy-punching (where one employee clocks in for an absent colleague).

Are there alternative methods that could achieve the same purpose? In almost all cases, yes. RFID cards, mobile apps, and PIN systems all record attendance. This is where most biometric systems fail the DPIA.

Even if biometrics are suitable and necessary, are they proportionate? Is the benefit sufficient to justify the privacy invasion and risk?

The Article 29 Working Party (predecessor to the European Data Protection Board) stated in Opinion 3/2012 that if the benefit is "relatively small (such as an increase in convenience or a small cost saving), the loss of privacy is not proportionate to the expected benefit."

Preventing buddy-punching and saving five minutes per day is a relatively small benefit compared to the permanent, irreversible risk of biometric data compromise.

Multiple AEPD enforcement actions have penalized companies for failing to conduct DPIAs before implementing biometric systems—or for conducting inadequate DPIAs that glossed over alternatives.

For example:

The pattern is clear: conducting a DPIA doesn't help if that DPIA inevitably concludes that less intrusive alternatives exist.

Companies defending biometric systems have tried various technical arguments. None have worked.

AEPD's Response: Biometric templates—the mathematical representations derived from fingerprints—are themselves special category personal data under Article 9(1) GDPR. The method of storage is irrelevant.

Even if you use advanced hashing, encryption, or one-way functions to convert fingerprints into numeric patterns, those patterns are still biometric data. The GDPR's definition explicitly includes data "obtained from specific technical processing relating to the physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a natural person."

That's exactly what a fingerprint template is: data obtained from technical processing of physical characteristics.

AEPD's Response: Following EDPS Guidelines 05/2022, both authentication and identification constitute processing of biometric data intended to uniquely identify a natural person. The distinction is legally irrelevant.

Whether your system searches a database of 10,000 fingerprints to identify an unknown person (identification) or compares one presented fingerprint to one stored template to verify claimed identity (authentication), you're still processing special category data under Article 9(1).

AEPD's Response: If biometric data was processed at any point—even momentarily to generate a template—you've triggered GDPR obligations. The duration of storage doesn't eliminate the fact that processing occurred.

Moreover, the AEPD has been skeptical of claims that biometric data is "immediately deleted." In the CTC Externalización case, the authority noted that the company couldn't demonstrate adequate security measures or provide convincing technical documentation about how the claimed immediate deletion actually worked.

AEPD's Response: Consent in employment relationships is presumptively invalid due to power imbalance. Additionally, if you need to offer an alternative to prove consent is freely given, that alternative demonstrates biometrics aren't necessary.

This argument has failed in every case where it's been attempted.

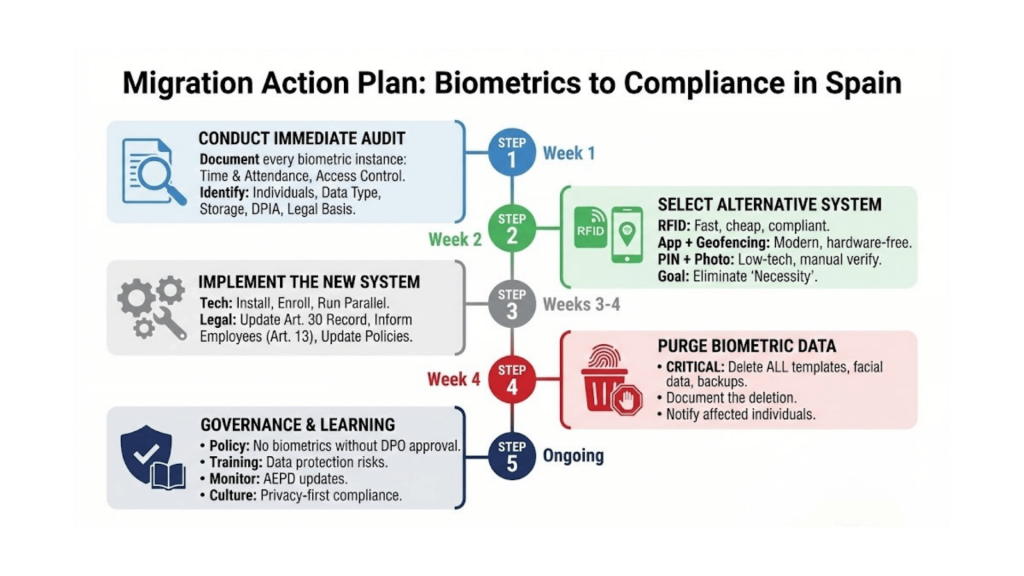

If you're currently using biometric timekeeping systems in Spain, you face a stark choice: migrate to compliant alternatives or risk enforcement action carrying fines up to 4% of global annual turnover (or €20 million, whichever is higher) under Article 83(5) GDPR.

Here's your step-by-step action plan:

Document every instance where biometric data is collected:

For each system, identify:

RFID Card Systems (Recommended for most SMEs)

RFID (Radio Frequency Identification) systems are the most straightforward biometric replacement:

Popular Spanish-compatible RFID systems include Jibble, Sesame HR, and Factorial (all offer RFID integration with cloud-based time tracking).

Mobile App Solutions with Geofencing

Modern smartphone apps offer sophisticated timekeeping without biometrics:

Popular options include Sesame HR, Kenjo, and Factorial (all Spanish-focused with English interfaces).

NFC Badge Systems

Similar to RFID but using Near Field Communication technology:

PIN Code Systems with Photo Verification

A low-tech but compliant option:

Technical Implementation:

Legal Implementation:

This is critical and non-negotiable:

You must permanently and irrecoverably delete all biometric data:

Document the deletion:

Notify affected individuals:

Inform all employees and former employees whose biometric data was processed that their data has been permanently deleted. This isn't legally required but demonstrates good faith and compliance.

Update your privacy governance:

Unless you're handling nuclear materials, biological weapons, or classified government secrets, you're almost certainly not exempt from this guidance.

If you genuinely believe your security requirements justify biometric processing, you must:

Even in high-security contexts, the trend is clear: the AEPD expects you to exhaust all alternatives first.

Article 9(2)(b) GDPR does allow processing when "necessary for the purposes of carrying out the obligations and exercising specific rights... in the field of employment" if authorized by law or collective agreement.

In Spain, Article 91 of the LOPDGDD specifically allows for collective agreements to establish safeguards for digital rights. However, the AEPD has ruled that this authorization cannot bypass the GDPR's "proportionality" requirement.

Even if a union agrees to biometric timekeeping, the system must still pass the necessity test. If a less intrusive alternative (like an RFID card) exists, the biometric system violates Article 5 (Data Minimization), rendering the collective agreement clause invalid in this specific context.

For a collective agreement to even be considered, it must be sufficiently specific. It must:

Generic clauses about "implementing appropriate attendance systems" won't suffice.

Proceed with extreme caution. The scenarios outlined in this "Special Situations" section represent extraordinary and narrow circumstances. Relying on either high-security requirements or collective bargaining agreements to justify biometric processing is currently a high-risk compliance strategy in Spain.

The AEPD's current interpretive trend heavily favours data minimisation over employer convenience or generalized security concerns. Attempting to utilize these exceptions without a robust, documented legal basis and a flawless Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) significantly increases your exposure to regulatory investigation and severe sanctions.

Do not make a unilateral decision that your organization qualifies for an exception based solely on this article. Before retaining or implementing any biometric system under the belief that you are an exception, it is mandatory to obtain a formal, written legal opinion from a certified Data Protection Officer (DPO) or specialized privacy counsel who has evaluated your specific operational context, technical architecture, and labour agreements against the latest AEPD criteria.

Let's put this in stark financial terms.

Cost of Continuing with Biometric Systems:

Cost of Migrating to RFID/NFC/Mobile App:

The math is obvious. Even a "small" €20,000 fine would pay for RFID systems for 7-40 companies, depending on size. And that's before considering the non-financial costs of enforcement action.

Moreover, compliant systems often integrate better with modern payroll, HR, and accounting software than legacy biometric systems—creating efficiency gains that offset the migration cost.

There is no rational financial argument for maintaining biometric timekeeping systems in Spanish SMEs.

Some business owners have expressed hope that the AEPD's position might soften, or that new technologies might make biometric processing compliant.

Don't count on it.

The regulatory trajectory across the EU is toward more restrictive biometric processing rules, not less. The proposed AI Regulation (now in final trilogue negotiations) will classify certain biometric identification systems as "high-risk AI systems" subject to additional compliance obligations, conformity assessments, and prohibitions.

Some developments to watch:

Emerging technologies allow generation of "cancelable" biometric templates that can be revoked and reissued if compromised. This addresses the immutability problem.

However, the AEPD's position on RBR is unclear. Even if templates can be cancelled, the initial capture still involves processing biometric data, which triggers Article 9(1) obligations. And the necessity test still applies—if RFID achieves the same purpose, why use RBR?

The Spanish government could theoretically amend labour law to include explicit authorization for biometric timekeeping with appropriate safeguards. This would potentially satisfy Article 9(2)(b).

However, there's no indication this is being considered. The political climate in Spain and the EU generally supports stronger data protection, not weaker. The Supera cases generated significant media coverage and public support for the AEPD's enforcement.

As other EU data protection authorities follow the AEPD's lead (Belgium and Italy have already taken similarly restrictive positions), we may see EDPB guidance that harmonizes the approach across all member states.

This would be disastrous for businesses hoping to argue that Spain's position is unusually strict. Pan-European alignment would cement biometric timekeeping as non-compliant throughout the EU.

The smart money is on compliance now, not waiting for regulatory reversal.

Yes, for the vast majority of businesses, it is a de facto prohibition. Since the AEPD’s November 2023 guidelines, biometric timekeeping fails the GDPR "necessity test" because less intrusive alternatives (like cards or apps) exist. Unless you run a high-security facility (like a nuclear plant), you cannot legally justify using biometrics solely for attendance tracking.

No. This defense has been explicitly rejected by the AEPD. The authority ruled that biometric templates—even if hashed or encrypted—are mathematical representations derived from physical characteristics and therefore constitute special category personal data (GDPR Article 9). Processing this data without a valid exception is unlawful.

No. In an employment relationship, there is an inherent "power imbalance" between the employer and the employee. The AEPD and the European Data Protection Board define consent in this context as "not freely given" because employees may fear consequences for refusing. Therefore, employee consent is not a valid legal basis for biometric processing in the workplace.

Previously, businesses believed that "Authentication" (1-to-1 matching) was safer than "Identification" (1-to-many search). However, the AEPD guidelines from November 2023 removed this distinction. Both authentication and identification are now considered processing of special category data and are subject to the same strict prohibitions.

Fines vary based on the severity of the violation and the size of the company, but they typically range from €20,000 to €1,000,000. Recent cases include a gym fined €27,000, a sports center chain fined €96,000, and an outsourcing company fined €360,000.

The AEPD recommends systems that do not process special category data. The most compliant and common alternatives are:

RFID Cards/Key Fobs: Cheap, fast, and privacy-compliant.

Mobile Apps: Using geofencing to verify location.

NFC Badges: Similar to RFID but using near-field communication.

PIN Codes: Ideally combined with supervisor verification or standard photo ID checks.

No. While preventing fraud is a legitimate goal, the AEPD rules that it does not pass the "Proportionality Test." The benefit of preventing a colleague from clocking in for another is considered "relatively small" compared to the high risk of compromising an employee’s permanent biometric data. Less intrusive methods (like supervisor oversight or cameras at the entrance) can prevent fraud without processing biometrics.

No official grace period was granted in the text. The AEPD has been actively enforcing these rules since the guidelines were published. Companies are advised to act immediately: conduct an audit, select an alternative, and migrate as soon as possible to avoid enforcement action.

You must permanently and irrecoverably delete all biometric data. This includes fingerprint templates, facial recognition data, and any associated records on the terminals, central servers, and backup drives. You should document this deletion process (dates, methods, authorization) as proof of compliance.

Exceptions are extremely rare and generally do not apply to SMEs. Biometrics might be justified only in critical high-security environments, such as nuclear facilities, biological weapon labs, or areas handling classified government secrets. Standard offices, gyms, construction sites, and retail stores do not qualify for these exceptions.

The message from Spain's data protection authority could not be clearer: biometric attendance systems are incompatible with GDPR for almost all business contexts.

The Supera precedent, the November 2023 guidelines, and the escalating enforcement actions have created a regulatory environment where continuing to use fingerprint scanners or facial recognition for timekeeping is not a compliance gray area—it's a countdown to enforcement action.

Every day you continue operating biometric systems without a legally defensible justification, you accumulate liability. The AEPD's enforcement has ramped up significantly since 2023, with investigations often triggered by employee or customer complaints. All it takes is one disgruntled individual to file a complaint, and you're facing an investigation that could culminate in a five- or six-figure fine.

The alternative solutions—RFID, NFC, mobile apps, PIN systems—are mature, affordable, and readily available. They integrate with modern HR and payroll platforms. They satisfy Spanish labour law requirements for working time registration. And critically, they pass the GDPR compliance test that biometric systems fail.

The transition isn't just legally required—it's financially prudent, operationally straightforward, and technologically sensible.

If you're still running fingerprint scanners in 2025, you're gambling that your business won't be the next enforcement action headline. The odds of that bet get worse every month as the AEPD intensifies scrutiny of biometric processing.

The death of the fingerprint scanner in Spanish workplaces isn't coming—it's already here. The only question is whether you'll migrate proactively or be forced to migrate reactively after an investigation, with fines attached.

Choose wisely. Choose compliance. Choose RFID.

AEPD Official Guidelines (in English):

GDPR References:

EDPB Guidance:

Spanish Labour Law:

Important Legal Notice: This article is provided for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. The content is based on the author's interpretation of Spanish data protection law and AEPD guidance as of January 2025. Data protection law is complex, rapidly evolving, and highly fact-specific. Reading this article does not create a professional relationship between you and ANRO Privacy or the author.

You should not rely on this article as a substitute for obtaining specific legal advice from a qualified Data Protection Officer or lawyer regarding your particular situation. Each business has unique circumstances, technical implementations, and risk profiles that require individualized assessment. What is compliant for one organization may not be compliant for another, even in seemingly similar situations.

Before making any decisions about biometric processing systems or implementing alternative attendance tracking methods, you must consult with a qualified legal professional or certified Data Protection Officer who can assess your specific requirements, conduct a proper Data Protection Impact Assessment, and provide advice tailored to your organization.

The author and ANRO Privacy disclaim all liability for any actions taken or not taken based on information in this article. Compliance with GDPR and Spanish data protection law is your responsibility, and you should obtain professional guidance before making compliance decisions.